Originally the brain-child of Pope Gregory IX and established in 1231, much has been written about this group of ideological bottom-dwellers. The later incarnation, called the Spanish Inquisition, was established by the Spanish Monarchy in 1478 to maintain Catholic orthodoxy.

The monarchy and church had powerful incentives for forcing everyone to adhere exclusively to Christianity. It gave Ferdinand ll of Aragon and Isabella l of Castile an increase in political authority and quelled social unrest. Repression of heretics (those who held opinions contrary to the Catholic Church) ensured only the most fundamentalist of clergy maintained power. Profits from the confiscated land and possessions of infidels and heretics also added more wealth to the royal coffers.

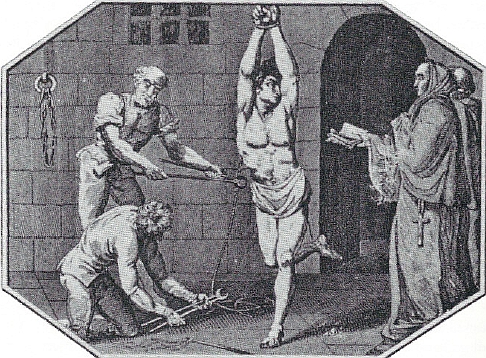

Appointed to weed out Jews, Muslims and followers of other non-Catholic faiths as well as converts still practicing the rituals and traditions of their former faith, the Spanish Inquisition encouraged people to snitch on their neighbors and tortured and exiled those who refused to convert.

In Andalusia, where people of different faiths had, for hundreds of years, thrived in relative peace, Jews and Muslims unwilling to convert were eventually purged from the landscape. Yet they left behind a legacy of art, literature, music, and architecture reflecting what had once been a flourishing period of ideological cross-fertilisation.

In The Infidel’s Garden, Rutger – our subversive dwarf – expresses his view on the whole business of religious indoctrination:

‘…peace and understanding don’t come through the brutality of conquest, but the gentle seduction of assimilation.’

After the reformation, the Inquisition added Protestants to their list of prey. Click on the link-star below for a more balanced and detailed perspective on the topic.